[wc_box color=”inverse” text_align=”left” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” class=””]

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. It is licensed CC-BY-ND. Click here for original.

[/wc_box]

Japan was the third-largest producer of nuclear power in the world in 2011. Then, on March 11 of that year, an earthquake of magnitude 9 was followed by a catastrophic tsunami, resulting in the first nuclear disaster of the 21st century – at the Fukushima Daiichi power station. The country’s nuclear plants were shut down, and within a year Japan had become the world’s second biggest importer of fossil fuels.

Before the tsunami, nuclear power provided 25% of Japan’s electricity, and a strategic plan was in place to expand this to 50%. Japan has few fossil-fuel resources of its own, so most of the resulting shortfall in electricity was made up by burning imported coal, oil and gas – an unsustainable solution from both environmental and economic perspectives.

But on a group of islands to the west, tidal power may offer part of the solution to the country’s energy needs.

A renewable future

By 2030, the Japanese government plans once more for nuclear power to provide around 21% of the nation’s electricity – which is highly controversial – but also stipulates (see page 8) that 22-24% should be delivered by renewable energy sources. At a local scale, two prefectural governments, Fukushima and Nagano, have pledged that all of their electricity will come from renewables by 2050.

Most of the new renewable energy available in 2030 is likely to be solar and wind, along with existing hydropower, but some contribution from the tides is possible. To this end, a zone in the Goto Islands of Nagasaki Prefecture has been designated for tidal energy development, and a cluster of companies plans to install the first turbine in 2019. This project will be of the tidal stream type, where underwater turbines are placed in the free flow without any dam or barrage, similar to the MeyGen project in Scotland.

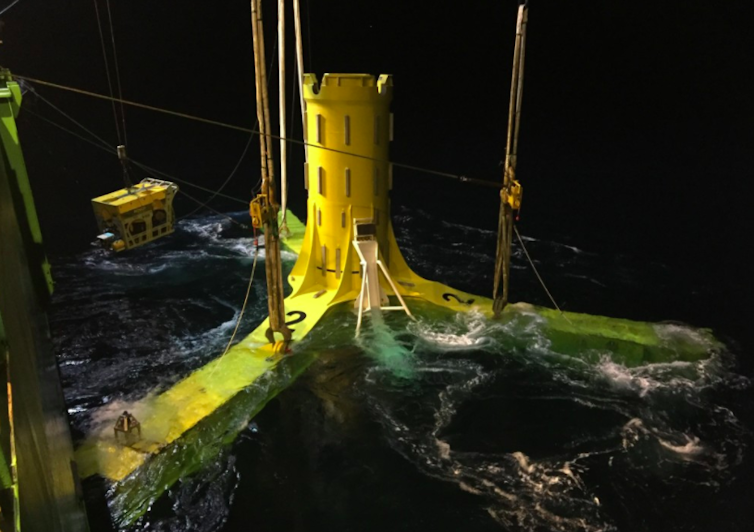

Installing a tidal stream turbine base at the MeyGen project off the coast of Caithness in northeast Scotland.

Installing a tidal stream turbine base at the MeyGen project off the coast of Caithness in northeast Scotland.

MeyGen/Atlantis Resources

When tidal turbines are placed in a channel, they remove energy from the flow. This causes it to slow, and represents a partial blockage of that channel. In turn, that means that the behaviour of the tides in an area after turbines are installed can be different to how it was before. Understanding and predicting this change is important for estimating both how much energy is available and the impacts of removing it; if there are too many turbines, the flow could slow too much and much less power would be generated.

Going with the flow

My recent work, in collaboration with researchers in Scotland and Japan, involved using a computer simulation of tidal flow around the Goto Islands to investigate the effects of installing large numbers of turbines.

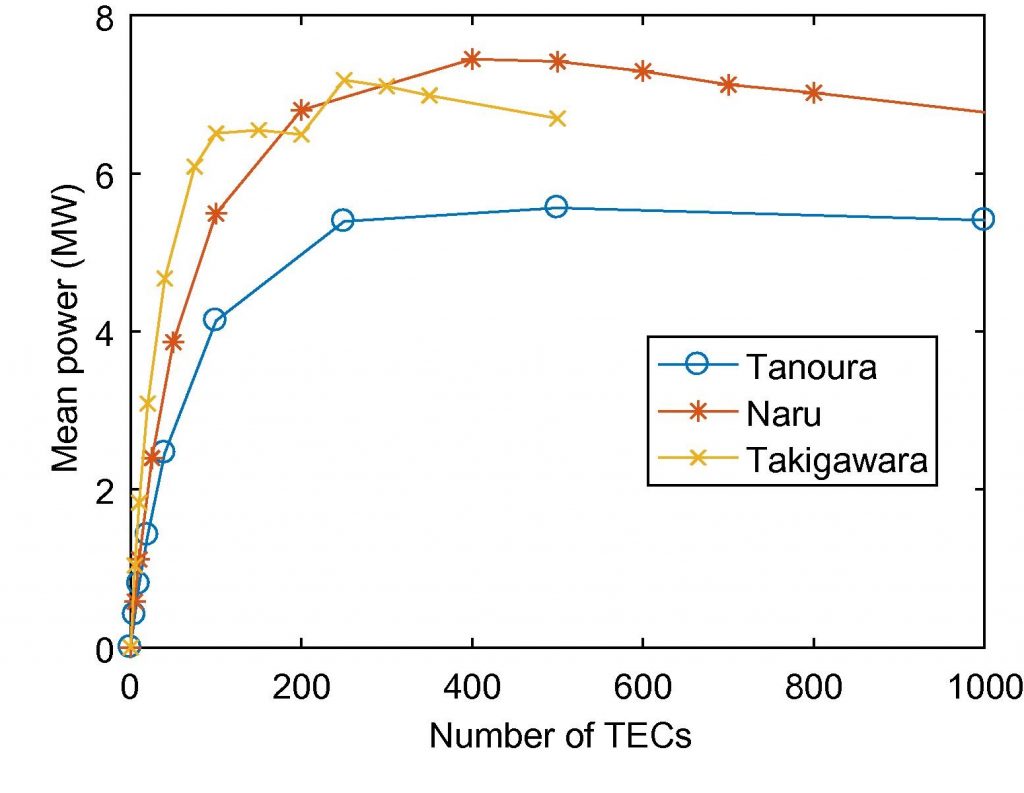

We estimated that between 24 and 79 MW of power could be generated from the designated area. The reason for this range is because the number of turbines that are used will ultimately depend on economic considerations. The first few will offer the most benefit, while later ones will suffer from diminishing returns. Tens of megawatts represents a very small contribution to Japan’s overall electricity needs, but a very large chunk of the local demand in these islands.

A number of parallel channels run through the Goto archipelago, of which two are within the tidal energy zone. In situations like this, it is common to find that adding turbines to one channel simply causes the water to flow by a different route. That means that to harvest energy efficiently we need to collect it from all the channels at once – an expensive proposition for a new technology.

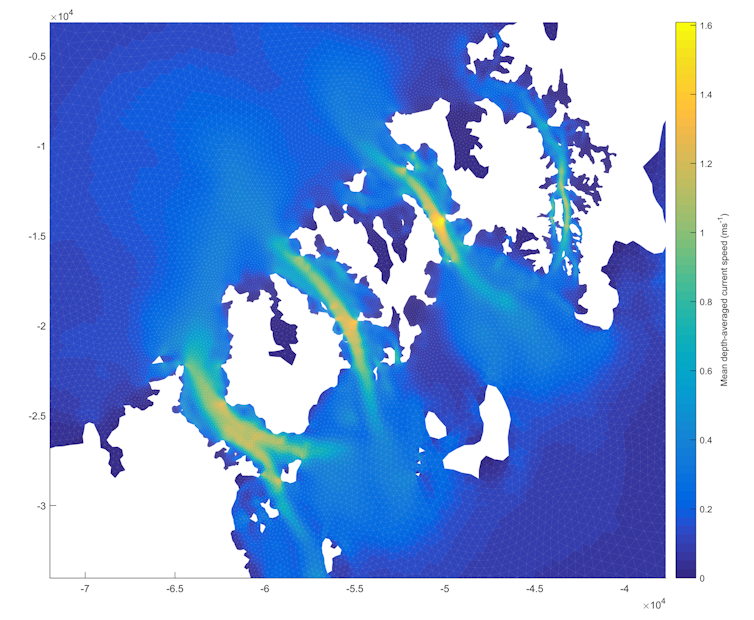

In the Goto Islands, all the channels run parallel but separate to each other, never merging or meeting, so they can each be exploited without affecting the others.

In the Goto Islands, all the channels run parallel but separate to each other, never merging or meeting, so they can each be exploited without affecting the others.

Elsevier, Author provided

However, our modelling shows (see sections 4 and 7.2) that the parallel channels in Goto do not behave this way; instead, they are independent of each other. The reason for this unusual behaviour lies in the geometry of the islands.

Partially blocking a channel causes water levels to rise a little behind the blockage. The interactions that we see elsewhere in the world are a result of this extra water “spilling” into other channels. In Goto, because all of the channels run separately from one end to the other without meeting or merging, and because their mouths are spaced well apart, there is no way for this “overspill” to occur. Consequently, any or all of the channels can be exploited without affecting the others, which should make the area more attractive for commercial development.

If the relatively small-scale development in Goto is a success, it could act as a proving ground and a springboard, leading to the use of tidal energy in other locations all over Japan. And for a country ambivalent about its return to dependence on nuclear power, additional contributions from renewable energy will be welcome.

![]()