There’s a… not quiet, but also not mainstream, debate raging at the moment, about how we’re going to heat our homes in the future. Actually it’s about how people who live on the gas grid will heat their homes, but that is the majority, and it includes most journalists.

An important caveat

I’m not an expert here – if I was, I would be writing a journal article rather than blathering on my blog – and I haven’t done the maths. I welcome correction by people who have.

From 2035 (earlier for new builds) people won’t be allowed to install new natural gas boilers in homes in the UK. There are a few possible ways of replacing them.

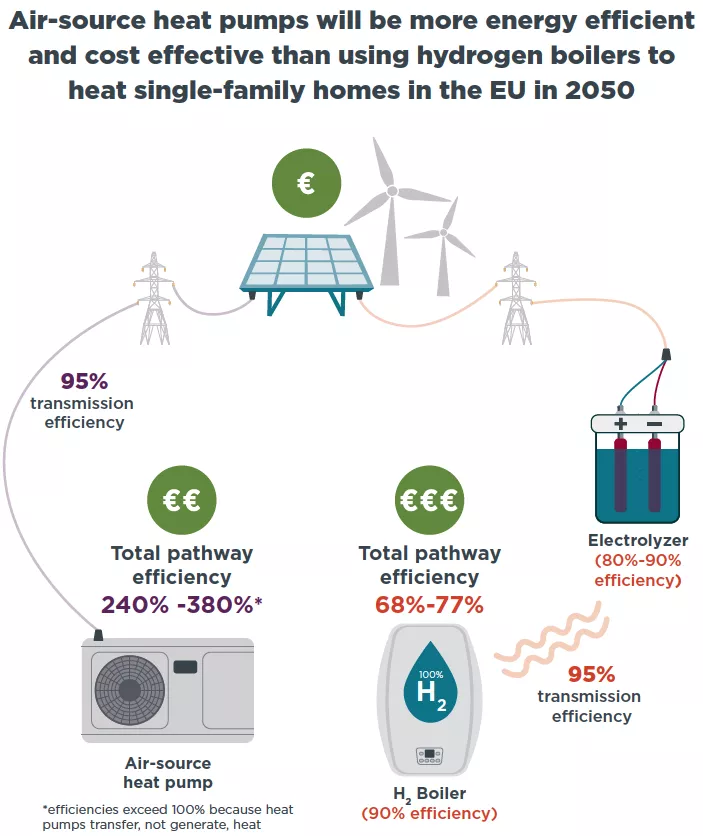

One approach, as with most things, is “electrify it, then use low carbon electricity”. In the case of the UK the answer to this is electric heat pumps, which are basically air conditioners run in reverse, to move heat from outside the house to inside it. They’re more common on the continent than here, but they’re reasonably common here in commercial premises and are becoming better known as a domestic option. Heat pumps are stupendously efficient[1], doing between 2.5 and 4 times better than a basic electric heater.

There are some disadvantages to heat pumps: firstly, that they’re not a direct drop-in replacement for a boiler. You need to find somewhere to put the unit that goes on the outside of the building, and because they don’t deliver water at such a high temperature as a boiler, poorly-insulated houses will need to be insulated better. In some cases they may need to have larger radiators fitted. The UK has a lot of poorly-insulated houses, although many would argue that insulating them better is one of the first things we should be doing anyway… Another difficulty is that we’ll need more low carbon electricity to power all these heat pumps, and we might need some grid reinforcements to deliver that power to where it needs to be.

The other approach that’s being talked about is using hydrogen, produced using electrolysis with renewable electricity. Replace gas boilers with hydrogen boilers – at worst a drop-in replacement, at best a simple adjustment – run hydrogen through the old gas pipes, and bingo, low carbon heating without much cost or disruption, and because we’re still sending the energy via the gas grid there’s no need for electricity grid reinforcement.

There are a couple of downsides to this plan. One is that it’s much, much, less efficient. The total amount of energy needed to produce the hydrogen and transport it is (very roughly) 4x the amount you’d use in a heat pump that was doing the same job.

The second problem is that renewable energy is a scarce resource. We’ll struggle enough to find enough to power all those heat pumps in the short or medium term, so we’ll struggle even more to find four times that much to electrolyse all that water into hydrogen.

And this is where it gets controversial. Instead of finding enough renewable electricity to produce hydrogen by electrolysis (so-called “green hydrogen”), we could make it from natural gas. The “blue hydrogen” concept is to continue extracting natural gas, and split it into carbon and hydrogen when it gets ashore. Put the hydrogen into the gas grid, and bury the carbon back under the North Sea using carbon capture and storage (CCS). It’s quick, relatively cheap, and uses existing infrastructure. It’s not forever, of course, because both natural gas and carbon sequestration space are finite resources, but it’ll tide us over until we can produce enough green hydrogen. Right?

The strongest proponents of this plan are, unsurprisingly, the natural gas industry (fascinating scholarly report from UKERC). The next strongest are politicans who have good relations with the natural gas industry, and would like to minimise disruption. There’s a lot of lobbying power there, and this is a tempting proposition. Some people look at this and say “it’s a way for the natural gas industry to keep going with business as usual, and lock us in to a whole new gas infrastructure in the process”. Blue hydrogen champions say “but what choice is there? You can’t build renewables fast enough otherwise”. They’re usually using a straw man of building renewables fast enough for green hydrogen, rather than simply electrification, but they might be right about that too – I’m no expert on build-out rates and supply chain limitations.

But if they’re right, and if they’re speaking in good faith, then surely there’s a way to get the same stopgap benefit as blue hydrogen without locking us into the hydrogen route in the long term? Use natural gas, and use CCS, just like with blue hydrogen – but when the gas comes ashore, don’t make hydrogen with it. Burn it in a CCGT power plant, with carbon capture, and then supply electricity. Sure, you lose 2/3 of the energy in the power station, but the efficiency gains in using heat pumps rather than boilers roughly cancel that out. In the future it’s easy to let renewables replace the CCGT+CCS, at which point we’re left with a much more efficient system. And in the short term the gas companies get to keep extracting – but without locking us in for the long haul.

I don’t see anybody recommending that. Maybe it’s because it still leaves the supply chain “problem” (people will argue problem vs opportunity), in how quickly we can get homes converted to heat pumps. Maybe it’s because it will still require electrical grid reinforcement. Maybe because the whole argument for blue hydrogen is being made in bad faith.

I honestly don’t know which. It could be all of the above! Or it could be something that I haven’t thought of.

[1] Pendants and physicists are correct that this isn’t actually an efficiency, it’s a Coefficient of Performance – and hence it doesn’t break any laws of thermodynamics for it to be over 100%.